“Sorry, I’m slow.”

I used to say this a lot — or variations of it.

Sorry, I’m feeling slow today. Sorry, I’m so bad at this. Sorry, I’m so much slower than everyone else. Sorry, this trail is really hard for me. Sorry I’m so slow, I had a crash and got my chain stuck and then you wouldn’t believe it, but I got chased by a rabid badger, but really, just, sorry for being slow. Blah blah blah.

It wasn’t really because I thought I was slow (although, sometimes I did), but because I was so often riding in situations where I was slower than everything else, or at least towards the back of the group. This is the reality of being a new racer and dating a male professional mountain biker who has lots of male pro biker friends. I knew this, on some level, but I still felt shitty every time people were waiting for me. Hence, the apologizing.

Sorry, I’m slow. Sorry you had to wait for me. Blah, blah, blah.

The problem with saying “I’m slow” all the time, whether you believe it or not, is that it’s pretty much the opposite of what you should be telling yourself if you want to race fast. Our friends in Santiago did an experiment where they put two kiwifruits in different jars and labeled one “beso” (kiss) and the other “poto cara” (butt-face). They kept the jars in the same conditions and three weeks later the butt-face kiwi is covered in mold and the beso kiwi is fine. Now, don’t ask me how that works, but apparently it does, and the point is — what you say, matters, and it matters a lot.

I’ve tried to stop saying stuff like this in the past, but it’s never really stuck, because when I get to the bottom of the trail and see a bunch of people sitting around tapping their feet, I feel obligated to say something. This is because I’m a woman and have been indoctrinated by society to think that the only thing worse than drowning puppies in a swimming pool is inconveniencing people. (To be fair, I’ve heard guys say “sorry, I’m slow” but not NEARLY as often.) But, in all seriousness, when you’re the last person to roll up, saying nothing feels like ignoring the big, purple elephant sitting on the side of the trail. You can’t just pretend nothing is going on. If you do, people will probably assume you’re pissed off and they’ll be all “are you okay? did you crash?” and then you will be pissed off, and probably say something testy like “no, I’m just actually this slow, believe it or not” and then everyone will feel awkward and you will feel bad about yourself, all over again. Not that I’m speaking from personal experience or anything.

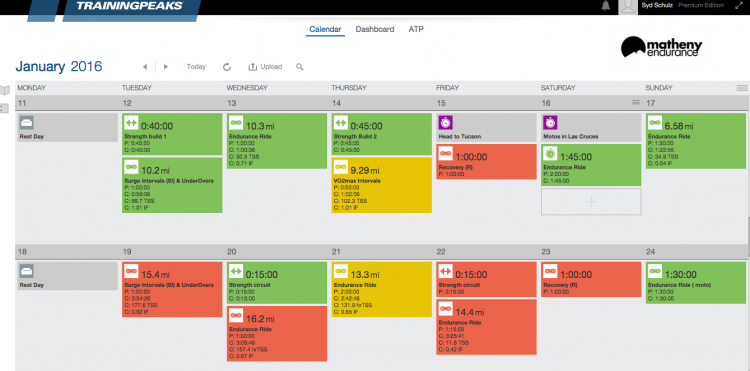

So, anyway, I was at an impasse — and then someone in my Facebook feed posted a link to this comic from Bored panda, called “Stop Saying “Sorry” And Say “Thank You” Instead,” and it was a massive lightbulb moment. It’s so good that I’m going to steal the first bit and post it below, and hopefully not get sued for copyright infringement. Seriously, though, you should go read the whole thing.

Via yaoxiaoart.com

And so, over the past few months I’ve made a concerted effort to replace “sorry I’m slow” with “thanks so much for waiting for me,” and the results are pretty astounding. (Obviously I should have titled this “She changes 3 words in her vocabulary and what happens next will amaze you.” I would have gotten a lot more clicks, missed opportunity.)

I first tried out this strategy on a moto ride, and the end result was having two motocross bros bending over backwards to help me dig my bike out of trenches and make it up hills, all the while constantly assuring me that this was the most difficult trail in the area (which does beg the question why they brought me on it on my 7th ever moto ride, but hey, we all had fun). The second test run was on a XC ride where I was seriously imploding and crawling up the hills. To be honest, I was going slow, but instead of saying that, I just thanked everyone for waiting for me and being so patient. It worked. Someone even said “it’s nice to ride with someone who just goes their own pace and has fun,” which was a nice affirmation.

Here’s why I think this works. When you thank someone for waiting for you, they feel good about themselves. They feel like they’re helping you out (which they are, of course), and doing a a good thing. They feel appreciated. And, to be honest, they probably had a fairly good idea of what your ability level was before they rode with you, so they probably knew they would be doing some waiting, and now they’re just happy that you’re appreciative of their time. When you say “sorry, I’m slow” it’s awkward for everyone involved. Whether you mean it or not, it comes off like you’re fishing to be told that you’re not slow, kind of like when you tell your boyfriend “my stomach looks fat in this shirt” and you really just want him to say “but you’re so skinny!” (Hint: don’t do that either.) The truth is, if they’re that much faster than you, they probably do think you’re slow. And they probably don’t care. And even if they do care? You shouldn’t care, because you know what — you’re out there, doing your best and it doesn’t make one iota of difference whether someone thinks you’re fast or slow or average or whatever. It changes NOTHING.

But when you thank people for waiting for you, or compliment them on how fast THEY were going, it turns the whole dynamic of the ride into something more positive. Not only do you stop sending yourself the wrong message, you make other people feel better about themselves and encourage them to help you with your riding, instead of just waiting and feeling awkward. In other words, everyone wins.