Last weekend’s Enduro World Series in Rotorua was hard.

You saw the pictures, so you know it was an unbelievable mud fest. You saw the stats — 8 hours, 64km, 7 stages, 6300 ft. So yeah, you know it was hard.

But what you couldn’t see — the mental game — was harder than all that. Yeah, the distance and the climbing and the horrendous conditions, they were all hard. And kind of more than what I was prepared for after having taken three weeks off to rehab my knee.

But, beyond all that, this was a race to see how hard I was willing to push myself simply to finish a race.

Not to do well — that was out the window within three hours after a mechanical on stage 3 and a missed start — but just to finish, most likely in last place. Physically, I was done at the bottom of stage 5. My equipment was also calling it quits. I had had a second mechanical on stage 5, or rather, a continuation of the same mechanical. To make a long story short, I made some poor equipment choices, as I expected the conditions to be similar to what they were in practice, or at least in the race in 2015. Which is to say, slippery, not clumpy. But we got clumpy, nasty, sticky clay and I had chosen a tire with not enough clearance in the front or rear (I wanted those big knobs for traction in slippery mud, and hadn’t thought about clearance), which resulted in both my tires clogging up and my chain guide getting so full of mud and pumice pebbles that it jammed with my cranks stuck at 12 and 6 o’clock, i.e. not what you want if you want any hope of navigating a technical trail with deep ruts. Then, to make matters worse, I crashed and my handlebars got stuck about 45 degrees off center, and I couldn’t ride at all, so I literally ran the last half mile of Stage 5. And by run, I mean, run five feet and then fall over, all while dragging my now 90lb bicycle, and being caught by the pointy end of the pro men’s field. Not my best moment on a bike, to be sure.

So there I was, at the bottom of stage 5, with one of the longest climbs of the race between me and stage 6, and then yet another climb after that. I had already missed my original start after stage 3 (and incurred a 10 minute time penalty), and I was in serious peril of missing the cut off and being told to go home. If there is something more demoralizing than hammering up an hour long climb, on a bike with an extra 20 lbs of muck, with only two functioning gears, being passed by the fastest men in the world, all without knowing if you will actually be allowed to continue the race if you do ever make it to the top, and knowing that they do let you drop, you will inevitably be the last finisher in the race — well, if there is a scenario less motivating than that, I have not encountered it (and I hope I never do).

A lot of shit went through my brain on that climb.

Why are you doing this?

What are you trying to prove?

Are you wrecking your knee?

Maybe you should just quit now so you can be be a DNF instead of last again.

You’re so much more prepared for races like this, why did everything still go to hell?

What will you do if they don’t let you finish?

Do you think they’ll let you ride all the stages after everyone, just to say you could do it?

For god’s sake what would be the point of that?

Would you really suffer that much for a result that wouldn’t count, just to prove you could make it around the course? What kind of fucking idiot are you? Are you really that stubborn?

Again, what the hell are you trying to prove here?

I thought your goal was to have FUN in this race, how’s that going, eh?

There’s no way you’re going to make your cut off, just stop now.

You just need to go a little bit faster, c’mon. Eat something and get it back together.

Am I lost?

No, there’s some tape. Just keep pedaling. You got this.

And then, finally, silence. It all just kind of went away. All my energy just went into turning the pedals.

I rolled through the aid station and passed most of the pro men while they got their bikes tuned up by their mechanics (must be nice, ha). I stopped only long enough to stuff my mouth and both fists with garlic bread, which I proceeded to half-eat, half-choke down on my way up the rest of the climb. I made my cut-off and actually almost made it back up to my original drop time.

That climb was the hardest I’ve ever done. Not physically, although it was up there, but mentally, because half of me was screaming “THERE’S NO POINT WHY ARE YOU DOING THIS” while the other half just kept saying “this is important, I don’t know why, but this is really fucking important.”

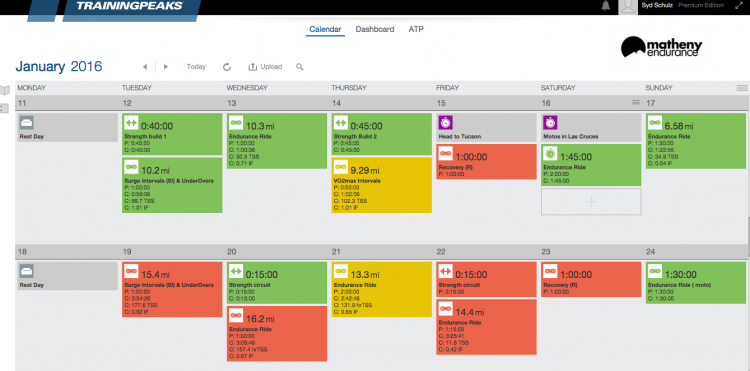

Sad drive chain :(

And ultimately, as I tried to explain to Macky at the finish line, I just seem to be willing to work very, very, very hard for the pleasure of being last in a bike race. I don’t think anyone would have blamed me for dropping out. After all, a quarter of the women’s field did, and I certainly don’t blame them. I could have said my knee was hurting (it was), or that my shifting wasn’t working (it wasn’t) or that I was afraid of hurting myself because I was so tired (also true). Or I could have just said I didn’t see the point because I had had two stages wrecked by mechanical issues and a time penalty on top of that. And it terms of results, yeah, there was no point. In fact, if I were thinking forward to my next race, it probably would have been smart to can it. My knee is definitely pissed this week, although I think it is doing fairly well given the circumstances.

In general, I’m trying to be more understanding of DNF-ing. I have had a tendency in the past to race through injury, or concussion, or sickness or any number of other un-safe circumstances. And ultimately, it’s a bike race — it’s not worth doing serious harm to yourself, or putting yourself back weeks in terms of health. This year I want to be smarter about that — I want to race with a long term perspective, and not feel like I have to prove something by dragging my broken body across the finish line.

And that was going through my head this weekend — maybe this is one of those times where it would be smarter to quit, my brain kept saying.

But it wasn’t. I wasn’t injured. I wasn’t sick. Nothing on my bike was broken except the shifting (and who needs that). Things just weren’t going my way. I was bummed. I was frustrated. But none of those are legitimate reasons to not at least try to finish the race.

If I had missed my cut off, I would have stopped. I wasn’t going to fight anyone to let me down the trail, and even though I entertained the possibility of riding the rest of the stages by myself, I was smart enough to realize that would have been unwise (and probably unappreciated by course marshals and medics who were undoubtedly just as eager to get out of the weather as we were). But I needed to at least see if I could make it. If I was going to go down, I was going to go down pedaling.

And yeah, I made it. Barely, but I made it. I finished the race. I was 29th out of 29 finishers (and 43 starters).

So, no, the result was not impressive. But the part of my brain that kept saying “this is important” was right. It was important. Why? Because we are capable of so much more than we think. When the brain turns off and we just keep going — the human body is amazing and can handle an incredible amount of pain and discomfort. Almost always it’s our minds that quit on us. That’s why finishing this race was so important. Not for the result, but because I thought it was impossible, and then I did it anyway.